A completely new type of headbutting dinosaur discovered in Mexico

Move over Pachycephalosaurus, there’s a new headbutting dinosaur from late Cretaceous western North America!

In a scientific paper published in January in the journal Diversity a group of paleontologists announced their discovery of a “thick-skulled theropod troodontid” from the late Cretaceous Period in Coahuila, Mexico. The paper’s lead author is Hector E. Rivera-Sylva from Coahuila’s Museo del Desierto. The full scientific article is currently available for free online via MDPI.

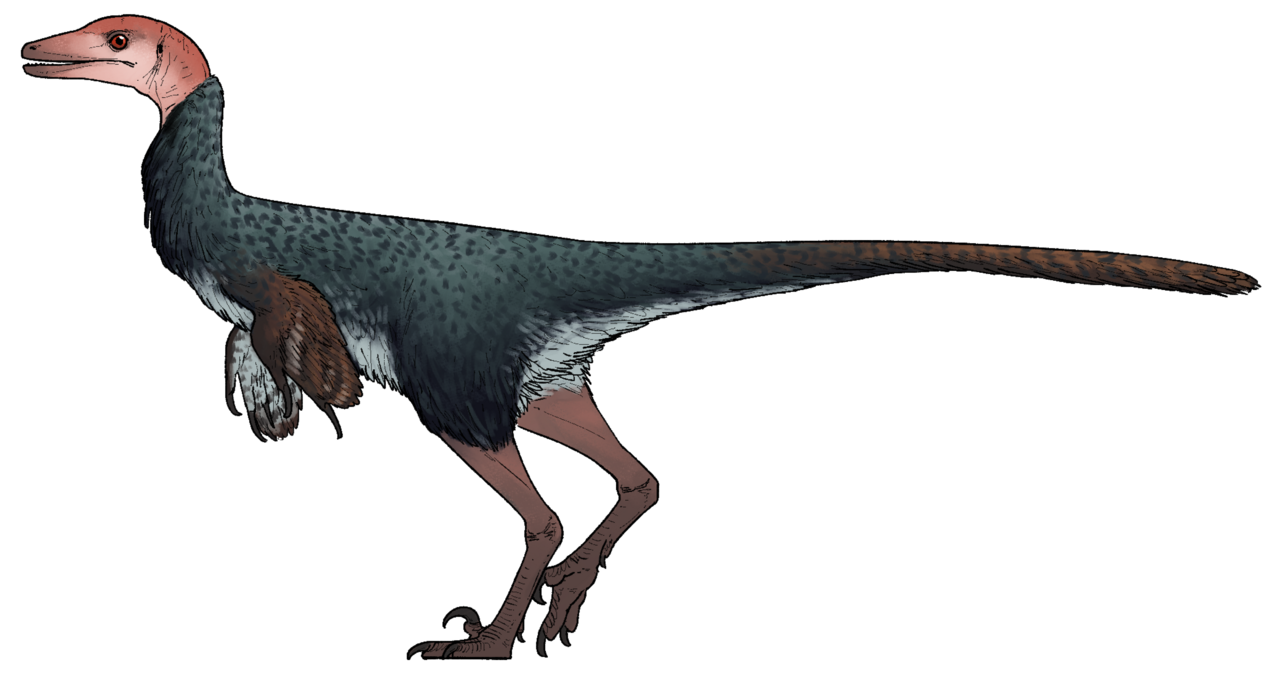

The new species, named Xenovenator espinosai, was described after a fossilized skull found in Mexico’s Cerro del Pueblo Formation. The Cerro del Pueblo Formation is believed to date back 74-73 million years ago to the Campanian stage of the late Cretaceous Period.

From their analysis of the skull, the authors believe that Xenovenator was a “troodontid” - that is, a relative of the theropod dinosaur Troodon. Detailed photographs of the fossilized skull are available online.

The paleontologists also reported on unique adaptations in this particular skull that might have allowed Xenovenator to headbutt, something previously unknown among the troodontids.

The new troodontid has a thickened cranial dome, tightly interlocking cranial sutures, and a rugose skull surface, features seen in animals that use the skull for intraspecific combat.

Headbutting in other animals

Headbutting in dinosaurs is generally associated with the thick dome-skull dinosaurs like Pachycephalosaurus and its relatives. However, other dinosaurs are believed to have been capable of headbutting, like Pachyrinosaurus, a relative of Triceratops.

Among living animals, headbutting is most prominent among mammals in the goat-sheep family, like bighorn rams and musk oxen. While these animals can use their thickened skulls to ward off predators, they are generally used in headbutting competitions among males to establish their right to mate with females.

Rivera-Slyva and his co-authors interpret a similar function for the thickened skulls in Xenovenator and other dinosaurs. They stated in the paper that “such structures likely evolved in response to sexual selection: they helped their owners find mates.”

Xenovenator is my favorite dinosaur!